Information and communication technology (ICT) lessons for primary schools, in Malta at least, must change. If there is even an inkling that primary school syllabi across the world aim to teach children how to retrieve files from CD-ROMS, how to work Word and Excel and make PowerPoints, practise technical skills using ready-made examples, this article might address your region, too. This is not to discard teaching children how to do spreadsheets or format Word content. However, digital media education goes well beyond ICT teaching as technical skills. Media education goes beyond that.

Three issues to consider

To bring up digitally literate children three issues must be considered first:

- ICT is not part of the ‘core‘ subjects in primary schools (at least in Malta; for UK computing is included in the core subjects from year 2 without assessment. For year 4, computing is not a core subject but ‘foundation‘ whatever the difference). The ICT currently taught in primary schools in Malta is misaligned from out-of-school practices and real life situations, detached from the social aspect of technologies, and limited as lessons focus mainly on technical skills;

- Inequalities will continue: it’s not about having access to technologies alone;

- Rich online and offline resources on digital media learning, skills and literacy do not reach or are used by as many parents as may be intended.

Digital media education, not part of the ‘core’ subjects yet

There is continuous talk, research, strategising and policy development in the effort to teach children digital media skills. This includes Malta. Copious amount of research is carried out internationally – a lot in the UK. Efforts on bringing up digitally literate children abound globally, too. Some efforts to bring up digitally literate children seem more targeted – focusing on teaching children how to code, learning through technology-mediated gamification. Others expand further by outlining key 21st century skills such as those of Henry Jenkins which include play, performance, simulation, appropriation, multitasking, distributed cognition, collective intelligence, transmedia navigation, judgement, networking and negotiation. All these skills can be addressed individually. Parents and children can also explore and learn these together.

However, how much primary schools teach children these skills, specifically those related to media, depends on what priorities each school places on the various other taught subjects. Usually, priorities fall on those ‘core’ subjects that also include end-of-term assessments. Any teacher can attest to that. This takes us to the bigger argument:

What are the ‘core’ subjects for primary education and why wouldn’t digital media education – or literacies – be part of that core?

Inequalities persist

The way children are currently taught ICT in schools potentially adds to the existing inequality gap, as is still evident, despite that digital media technologies have the potential to remedy this.

Why the gap is likely to persist as a result of limited or poor ICT teaching in school? Because those more privileged children are more likely to have better and bigger opportunities outside school by having extra curricular activities and perhaps, thanks to more educated and media literate parents, too.

Rich online and offline resources, yet not everyone accesses or makes use of them

While there is copious amount of research, advice, material of all kind online, there are still many parents who do not access or make use of this material. For my doctoral thesis I interviewed over 300 parents in Malta (and counting). Many would resign to general worries of possible negative consequences from using networked devices thus would limit their child/ren’s digital media use. Many wouldn’t have checked the amount of resources available on their Ministry for Education website or elsewhere to get good ideas for co-use, for educational purposes, for enable creative exploration or to encourage their children to pursue their interests and so on.

There is a growing amount of material on- and offline that promotes from fostering creativity, acquiring technical and technological skills, to safety and protection, to various games and apps and so on. While research may influence, direct or help policy makers who in return can adjust and build new frameworks, guidelines and rules, from my conversations with parents, it seems that many still paddle on rather confused and often worried, having not much time to go on all the overwhelming sites to look up ideas and structure their digital media ‘diets’ to maintain healthy digital lives in their homes.

In short, having the guidelines and the information online is just not enough.

Make a parallel with food and the result is similar. So much research is carried out and available in all kinds of format and on many platforms. Media make headlines with every research carried out. Films (check “Forks over Knives” and “What the Health”) try to popularise the evidence albeit never criticism-free. National guidelines for nutritional and healthy eating are re-drafted. All kinds of initiatives take place to instil nutritional and healthy eating in schools and at home in Malta and elsewhere. Yet, a walk around state, church and private schools during lunch-time, I cannot help but notice the amount of children who eat cereals out of boxes, ham and cheese sandwiches and processed food that is clearly not nutritional and unhealthy. At play parks, I have seen children drink energy drinks and soft drinks and ice-teas; eat processed food such as chips and cookies. At restaurants many children (mine too) are handed ‘children’s’ menus that often contain chicken nuggets (whose contents are highly questionable) and chips which also come with a big health warning sign. In other words, the warning and the initiatives are there, yet change seems to either take at a glacial pace or not everyone – parents that is – makes use of, takes a heed on or accesses the available information – evidence and guidance.

The same way, despite the availability of research evidence and valuable resources online, many parents continue to worry about screen time and the various threats or negative consequences emanating from networked technologies taking no heed on the various nuances surrounding such concepts as threats, risks, and negative consequences. Many parents I have spoken to consider screen time disregarding the content, context and circumstances in which their children may seem ‘hooked’ onto a screen. Many parents I have been approached by, as elsewhere, seem to expect “black and white answers” regarding what, how and when to introduce digital media devices to their children.

This leads to the question:

How do we enhance and support that parental mediation which may not be aligned with research evidence or where parents simply lack the time or motivation to explore and co-learn digital media skills with their children?

While the issue with parents not making full use of the online resources and not taking a heed to research evidence before they believe the latest newspaper article on Internet ‘addiction’, may put more pressure on schools to bring up digitally literate children, it doesn’t have to be like that. Ultimately, it is a collective responsibility to bring up digitally literate children. Everyone is involved. Schools – teachers, principals, educators, and educational policy makers – must make the needed change.

ICT teaching must change. It must become enriched, more student-led, aligned with out-of-school practices, include students’ perspectives and interests, and provide opportunities for self-organised learning and making.

Malta is one of the few countries which does not often resort to student-oriented teaching practices making lessons strictly guided and structured by the teacher, with less participation and active involvement from the student.

This first and foundational step which makes it also my personal goal can begin by restructuring the ICT syllabus for primary schools. The current syllabus can therefore take a different course with learning objectives that can encompass more than technical skills.

From the current learning objectives:

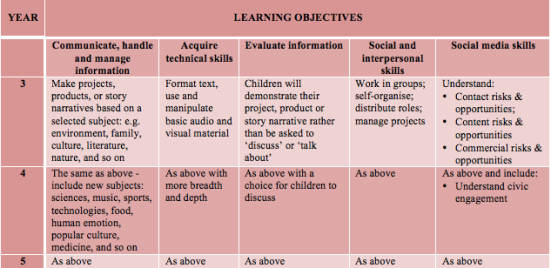

ICT syllabus’s learning objectives for years 3, 4 and 5 (7-10 years) in Malta

ICT lessons can change to this:

Making stories and learning social, technical and technological skills. (1) choose a theme: for example, a particular sub-topic from the environment, or literature, or health and nutrition, or astronomy and so on; (2) select the tool: for example a video app, an audio app for making a podcast, or an app for making a digital journal and so on; (3) group with peers and make the story; (4) demonstrate; (5) reflect. Start a new project.